Exhibiting Dovetailing at the Windermere Jetty Museum this year gave me the opportunity to spend time in the museum with its adjoining boatyard and conservation workshop, and to get a sense of fleeting movement, floating reflections, the forming of wood, and working with air and water.

I am drawn to the idea of wake, – traces left behind by disappearing presence, – and am gathering studies of varying kinds of wake as the starting points for a new body of work:

Wake from oars (taken by Adam Gutch)

I have started creating shapes from the the patterns and rhythms made by oars dipping in and out of water.

Traces of lines and light, boathouse, Jetty Museum

The large boathouse next to the museum is mesmerising, with splintered light filtering through the ceiling and muffled sounds of echoing water, and I love watching the tiny water boatmen draw rippled lines with their paddle-like back legs as they go, disrupting the flickering reflections.

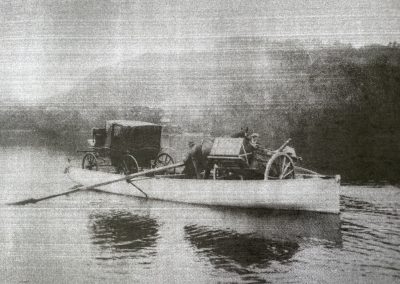

Wake and memory, Ferry Mary Anne

My imagination has been caught by the story of Ferry Mary Anne, salvaged from Lake Windermere in 1978 and currently undergoing a long and careful process of conservation. Built of larch, Ferry Mary Anne, the earliest-surviving rowing ferry boat (built between 1799 and 1860), now rests quietly on a custom-made cradle at the Windermere Jetty Museum, where her moisture content is closely monitored to ensure that there is no further decay.

I am drawn to how Ferry Mary Anne, which no longer makes physical wake, has a resonant presence in her stillness. The hull has degraded but enough remains to convey a sense of her movement across water which she was so regularly used for. There is a vitality in the ageing wood, and she is still able to transport us into a sense of her history, the poetry of the time (the Wordsworths used the crossing at Ferry Nab), the trees from which she was made, the skills and craft used to build her, and other lives lived on her journeys. I also love how the wooden structure has now become home for other kinds of life.